AI Perception Gap: From Tragedy To Closure — How AI Identified Plane Crash Victims

The Story Behind The Crash

Introduction

On July 17, 2014, a Malaysian Airlines passenger jet was shot down on its journey from Amsterdam Schiphol Airport to Kuala Lumpur. The plane was flying through Ukrainian airspace, 50 km from the Russian border, when it was struck by a surface-to-air missile over a region controlled by Russian-backed separatists during the war in Donbas. 298 victims were tragically killed. Identifying and returning body parts to loved ones was a formidable challenge as unidentified human remains (UHR) were dispersed over a 50 square kilometre region. Meanwhile, heartbroken families across the globe were grieving. Aware that each passing day without a burial added to the immense trauma experienced by the victims’ families, investigators looked to AI to help with returning UHR to loved ones as quickly as possible.

The Challenges

Investigators at the Netherlands Forensic Institute (NFI) were tasked with the difficult identification process. Frustratingly, they faced a number of obstacles.

- DNA quality: Fire and explosions during the crash meant remains were heavily burned, thereby degrading DNA.

- Site accessibility: The remains were spread across an active war zone which presented obvious accessibility issues. Body parts continued to arrive in the Netherlands for 10 months.

- DNA history: Investigators lacked prior records of the victims’ DNA, as they were not part of any criminal database. Identification had to be performed by DNA comparison with relatives. DNA donations were limited in some cases due to the death of immediate family in the crash or a lack of contact with other family members.

- Volume: Matching body parts by DNA requires a number of comparisons proportional to the square of the total body parts needing identification. 10 victims in a Blue Wing Airlines crash on April 3, 2008, were identified by manual DNA comparisons. This took 2 days by hand. However, with 298 victims, investigators at NFI faced the monumental task of making millions of DNA comparisons—a scale that made manual efforts entirely impractical.

The investigators needed a comparison-based identification framework that offered flexibility in terms of the number of DNA donations and the relationship of the donor. Most importantly, the system had to perform identifications as fast as possible!

The Solution

Fortunately for the NFI, they had a state-of-the-art forensic software system—named Bonaparte—developed by a team at Radboud University in Nijmegen, Netherlands, during the mid-2000s. The system, which was designed to facilitate quick human DNA-based identification, was the perfect solution for the investigation as it overcame the challenges presented above. It enabled the identification of body parts even in the limited setting of partial DNA matches due to fires; it facilitated DNA donations from multiple family members with great flexibility offered in terms of relationship with the victim (the more distant the relation, the less similar the DNA); and the digital nature of the system permitted 1000s of DNA comparisons in minutes.

After analysing 6,000+ UHR body fragments and 500+ reference samples from relatives, 294 of the 298 victims had been identified within four months of the crash. Another two victims have since been identified, whilst the remaining two have sadly vanished without a trace.

The Technology

Identification by Cause and Effect

Consider the sentence: “10-year-old Ben Barlow hit the football towards his grandparents’ window and the window smashed.” To the great annoyance of my grandad, who was celebrating his 70th birthday at the time, this statement holds true. After observing the cause (Ben kicks the ball), we can estimate the probability of the effect (the window smashed). Human cognition works in this direction.

But, given the effect “the window smashed” (and my grandad spent the afternoon of his birthday boarding up a window whilst all the family went out to celebrate), we need much more information to deduce the cause (who kicked the ball that broke it or even the fact that it was broken by a ball in the first place). Human cognition struggles to work in this direction.

This cognitive asymmetry was overcome in the 1700s when theologian Thomas Bayes proposed a new rule to employ when working with probabilies. Using the rule—now known as Bayes’ Theorem—one can work in the natural cognitive direction by estimating the probability of the effect given the cause, and use mathematical tools to infer the probability of the cause having observed the effect. This process is referred to as inverse probability.

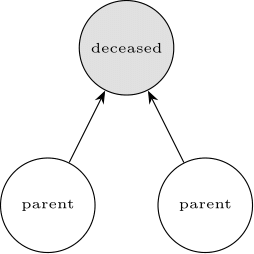

Now, in the context of identifying human remains: If person A and person B are the mother and father of person C (the cause), then matches will exist if we compare the DNA of the child with its parents (the effect).

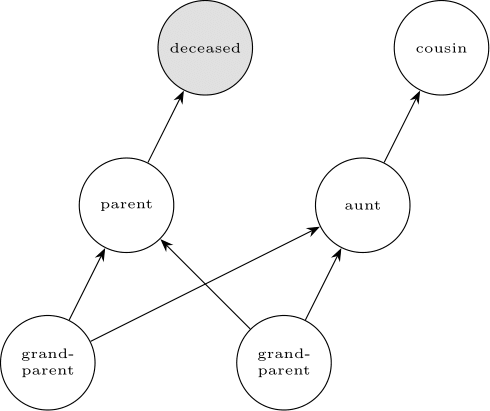

Expanding on the network of three nodes and two arrows, Bonaparte built much bigger networks (entire family trees). This allowed DNA donations from cousins, aunts, and other relatives, not just parents. When comparing all relations, Bonaparte was given the effect and used inverse probability to determine the probability of the cause.

A single UHR fragment was identified by the investigators by iterating through all 298 pedigree trees built using Bonaparte, entering the fragment’s DNA into each tree and observing the probability of the cause given the effect. By considering the trees that offered the maximal probability of the cause, the body part could be identified.

The Story Behind The Technology: How Neuroscience Can Inspire AI

Bonaparte proved to be an indispensable tool for the investigators. It offered flexibility in the number of DNA donations and the relationship of the donor whilst possessing the ability to infer the probability of the cause after being provided the effect. This was all made possible by the technology that underpinned Bonaparte: Bayesian networks.

Over two centuries after Thomas Bayes’ (1702 - 1761) work on cause and effect, along came Israeli-American computer scientist and philosopher Judea Pearl (1936 - present). Whilst you may not be familiar with Pearl, you’ve likely heard the phrase “correlation, not causation”. Pearl spent his academic career developing mathematical tools for causal reasoning; we can now make “X causes Y” conclusions rather than being limited to “X correlates with Y”. During his academic journey, Pearl invented Bayesian networks and because of their dependence on inverse probability, Pearl honoured Bayes by naming the framework after him.

Pearl’s breakthrough was a prime example of how neuroscience can inspire AI. His eureka moment came in the mid-80s whilst reading an article by David Rumelhart: a cognitive scientist at University of California, San Diego. The article highlighted when humans read, we first recognise lines and circles which we combine to form letters; these combine to form words at the lexical level which are passed to the syntactic level. It is here, for example, that we decide to expect a noun to follow the word “the”. Finally, we reach the semantic level, where we remember the previous sentence referenced a Volkswagen, so we predict the noun following “the” could be “car”. Climbing the ladder is permitted by information moving through layers of neurons in the brain.

All the while, information gets propagated down the neural ladder too. When we struggle to read poor handwriting, the syntactic and semantic levels provide context, which helps us recognise messy shapes, letters, and words. The key here is neurons in the brain are passing information in both directions (from the top down and the bottom up) and from side to side. A change in belief in one neuron has the ability to affect the state of all other neurons.

Pearl was convinced that for computers to reason well under uncertainty, they must adopt a structure similar to that of human neural information processing. It took Pearl a few months to figure out that messages between layers should consist of forward probabilities and inverse probabilities computed using Bayes’ framework. By the late 1980s, his students and colleagues had helped him create a tool that would accelerate the world of machine learning.

In 2011, Pearl won the Turing Award—the highest distinction in computer science—for “fundamental contributions to artificial intelligence through the development of a calculus for probabilistic and causal reasoning”. Without his contributions, the field of AI would be lacking many of the tools it has available today, and the families of the plane crash victims would likely have waited much longer to bury their loved ones, or not even been able to bury them at all.

Appendix - A Note On AI

As discussed in AI Perception Gap: Introducing my new blog!, my goal is to close the AI Perception Gap. In June 2023, whilst writing this blog in Valencia, my flatmate asked, ‘Artificial intelligence isn’t here yet, is it?’ Well, every day I walk past a sign which reads “Celebrating 60 years of research in computer science and AI at the University of Edinburgh.” This announcement states, “the University of Edinburgh traces the origins of its activities around AI to a small research group established in 1963”. AI has existed for decades, with Bayesian networks as an example of 1980s technology that remains state-of-the-art today.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: